Data's moral dilemma

The technical innovations of the last several years have led to the reality that a broad section of people are now coming into contact with AI systems whose behaviour can no longer be mechanically predicted. While self-learning systems previously had been a playground for researchers in labs for decades, they have now entered people's everyday lives with driver assistance systems for electric cars, for instance, as well as generative AI such as ChatGPT. Whereas in the past, errors in designed systems were always clearly the fault of the engineer who built them and their backers, society now has to deal with the fact that the decisions made automatically can be one way or the other, sometimes even harmful, and no one is responsible. Why this is the case is explained by old ethical issues - such as the legal handling of dilemma situations.

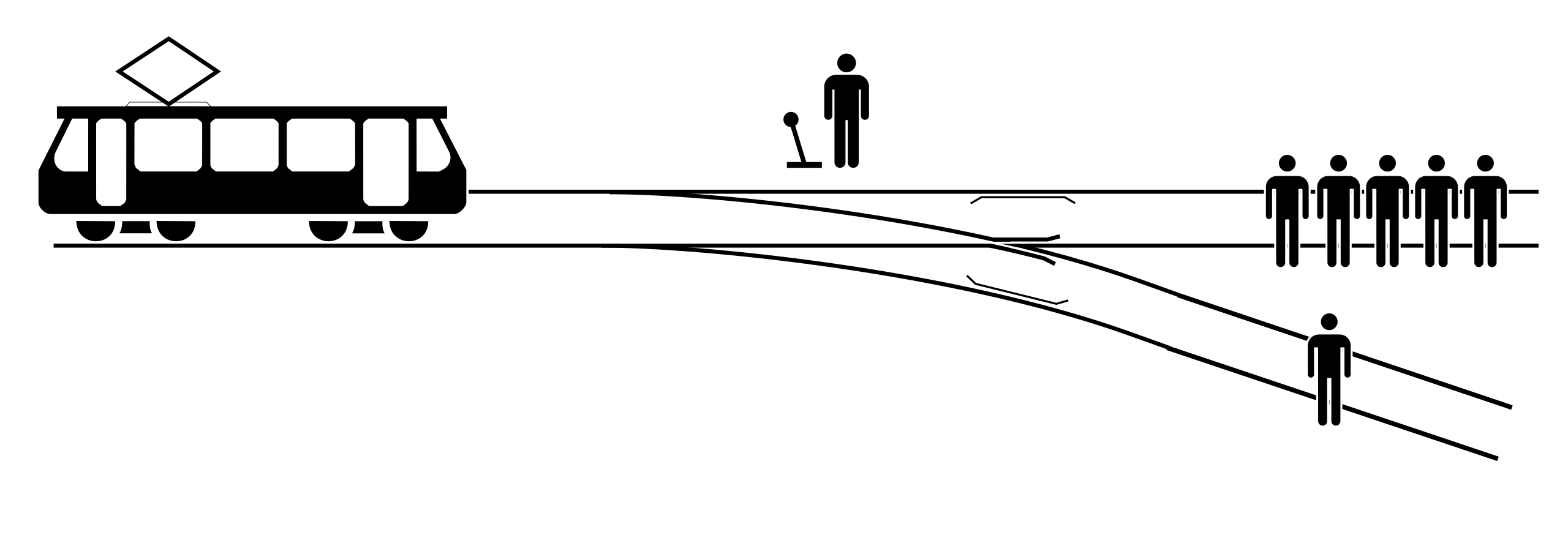

Before turning to Data, here is a brief reminder about what dilemma situations are. These are situations in which one has the free choice of a decision, but both decisions have negative consequences. How people deal with this has been studied in psychology with the trolley problem and its variants. In this case, a train is heading towards a crowd of people, but there is the possibility of setting a switch to avert this consequence. However, there is also a person on the other track who is endangered. What should be done?

Well, this is certainly a situation that has no clear solution. Here one is looking for and asking about clear guidelines that people can use, whether consciously or unconsciously, that will lead to deliberation and responsible action. With the advent of complex systems, guidelines should actually be taught to automatic systems. But the question is which ones?

What we already know from previous research is that there is no form of universal morality present here. The trolley problem already showed that people in Europe and the Western world try to count how many people will be killed and attempt to save the greatest number of humans, and in the example shown, the majority tend to throw the switch. In other cultures, however, people try to avoid actions that could harm or even kill people, with the resulting accusations. There, the majority will not change the switch, and can thus avoid responsibility for the consequences. If certain individuals and specific cultures already are mentally and ethically predisposed in a certain way, then a global debate likewise cannot produce a clear result.

Through technical evolution, these questions are now also raised for the decisions made by complex systems. For, on the one hand, technical systems are supposed to make people's lives easier and reduce hazards but, on the other hand, technical systems are only accepted if they are better than humans when faced with complex situations - and thus also act according to a higher moral standard in dilemma situations. Atleast achieving a higher percentage of favourable outcomes in such situations.

Instead of approaching the topic abstractly, one can also watch an episode of the series Star Trek Enterprise (Startrek The Next Generation), which stirred up a lot of viewers emotionally. In the episode "The Most Toys", first broadcast in 1990, the scriptwriters dealt with the old question in a more multilayered way. The starting point is a villain "Fajo" who has no classic evil aims, but who, in his lust for collecting, simply doesn't care about the ethical concepts of others.

This includes the fact that he also imprisons people like Varria and

the android Data and goes on to present them as part of his exhibition.

In a discussion between Fajo and Data, this sets up the moral dilemma

that occurs later on- when asked about actions and consequences, Fajo

asks the question "have you killed yet?". Data answers: "No, but I am

programmed to use deadly force for the cause of defence." With this,

Fajo is sure that Data cannot kill him unless he threatens him directly.

In the following scene, Varria and Data both try to escape. However, Fajo catches them both and Fajo decides to kill Varria in front of Data. Afterwards, he throws the weapon away - so he stands unarmed in front of the android, whose highest guidelines include that he may only kill in defence. But Fajo wants to exploit the situation much further - he wants Data to bend to his will and announces that if he does not join in his exhibition, more people will die. Here .... Data now has to weigh up. He finally says the key phrase "I cannot permit this to continue," and raises his gun to fire.

But the scriptwriters added an interesting twist here. No shot is fired and instead Data is beamed back to the spaceship at that very moment. The technician claims that the weapon is active and switches it off. Ryker, the officer in charge, asks Data about it, to which he replies "Maybe something occurred during transport.". The viewer is now left with the question - did he shoot and lie? And then of course - why? And why is this all accepted by Ryker?

Behind all this, of course, lies people's desire for safety. Living together with machines requires that they cannot become dangerous to us. Time and again in the series, it is shown that the android Data fulfils higher moral requirements than the error-prone humans around it. A machine that kills on account of mere calculation would always be disturbing, even though the decision in the episode is comprehensible to the viewer. The moral standing of Data in society is ultimately more important than the use of weapons in and of itself.

Not worrying people and making robots seem fundamentally harmless to them, is a very old concept, by the way. This was formulated by Asimov as early as 1942 in the "Robot Laws" of a novel, which were internalised by subsequent generations of engineers. In a later novel, Asimov then adds a "Zeroth Law" that stands above all others: "A robot must not harm humanity or, through passivity, allow humanity to come to harm."

In fact, however, that is exactly what is already happening. Self-driving cars have already simply run over people in the course of test operations. As a result, the question of liability was submitted to the German Ethics Commission, which then literally said in 2017, "We will end up in many classic dilemma situations," and did not draft a final guideline. Instead, they worked out philosophically that if two wrong decisions are made, no criminal charges may be made - so it is precisely not incumbent on the state to fight against the machine's wrong decision, no matter which one is chosen.

This may upset us because it appears that the manufacturer is being removed from liability for the product. The risk is then transferred to the owner, who, however, cannot influence it at all. Of course, this is not desired, but the manufacturers can ask about what these guidelines should look like, which they should then implement. This in turn puts a demand on society to decide as soon as possible on weighting factors about human life, why some people appear to be less worthy, why they are ultimately discriminated against, and why some groups of people are marginalised in real terms. The philosopher Lutz Bachmann gave an example, a new take on the old trolley problem, by posing the question of "who am I more likely to kill: the young family or the pensioner to my right?"

References:

Zeit (2017). "Wir werden in vielen klassischen Dilemma-Situationen enden". https://www.zeit.de/gesellscha... (accessed 25.06.2023)

YouTube (2023a). Star Trek STNG Moments 70 The Most Toys. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_skkBMvlWBw copyright Paramount Picture (accessed 25.06.2023)

YouTube (2023b). Have you killed yet. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xgKx1f3aemA (accessed 25.06.2023)

Photos: Teaser – “Data“ copyright Paramount Pictures (YouTube, 2023b)

Header : Freepik Hyperraum

Write comment

Your email address will not be published. Comments are published only after moderation.

Comments ()